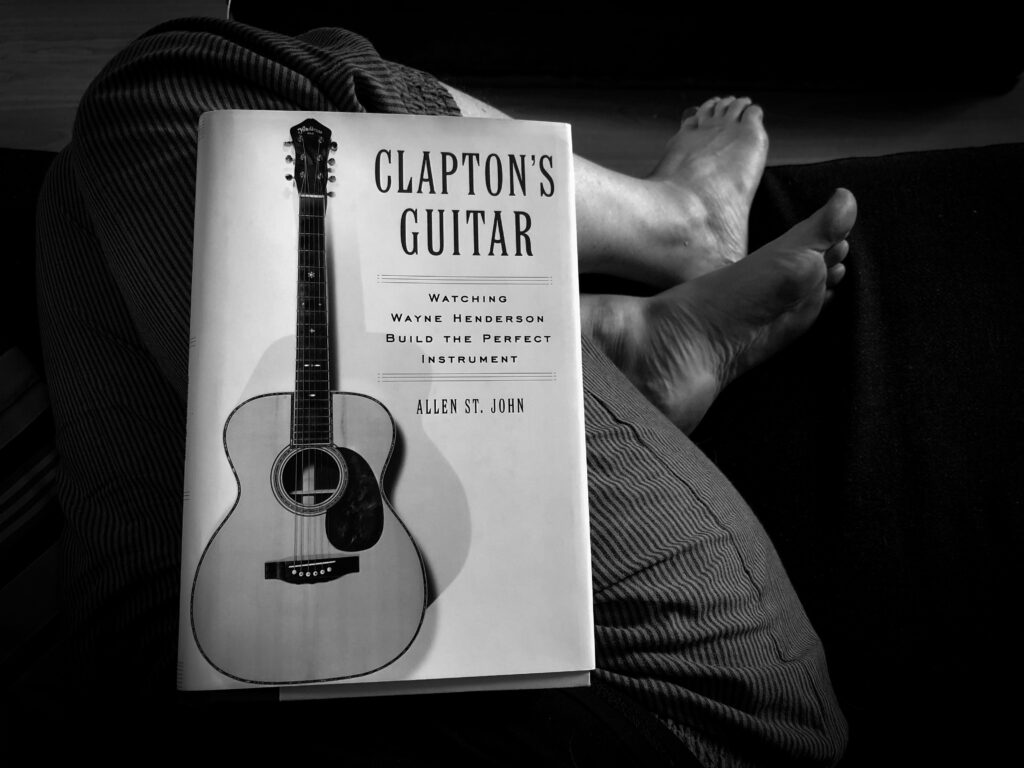

In 2015 I listened to a riff from Jonathan Fields on Good Life Project, telling a tale about one of Eric Clapton’s guitars. It must have stuck with me (things have a habit to do just that), because when I stumbled upon a book entitled Clapton’s guitar – watching Wayne Henderson build the perfect instrument, by Allen St. John, in a thrift shop in Karlskrona in 2018, I bought it. And now, in 2019, I’ve read it. And what a read it’s been!

There’s this one thing that fascinates me. Professionals. It doesn’t really matter what the profession is, but someone who’s a pro just gets me going. I’ve blogged (and vlogged) about a few of them; massage therapists, physiotherapists and chiropractors, train conductors and smartphone salesmen.

This book. It’s about a pro. Or rather, about pros. Not just the one. There are many a professional featured in this book, but more than anything, it’s about Wayne Henderson, a master acoustic guitar builder. A luthier.

“[…] Wayne Henderson is a genius. His brand of genius harks back to the word’s unsullied origins: the Roman term for ‘begetter’. In the days of Ceasar, a genius wasn’t something you were, it was something you had. A genius was a vaguely protective being like a guardian angel, but most of all this Roman version of a genius was a maker, a conjurer, a genie, who could create very real things out of thin air. And in that old-school sense of the word, Wayne Henderson has a certain genius, an ancient forest nymph that sits on his shoulders and whispers directions every time he picks up a piece of wood.”

And I love it. What a joy, a thrill, a treat, to read this book! I don’t understand the half of it, now and again, when it comes to the technical terms for all of the parts and steps that make up building a handcrafted acoustic guitar but it simply doesn’t matter. I am enraptured anyway.

“Every guitar has its own voice, an individual timbre that’s as distinctive as a human voice – there’s no doubt that some techie could program voice recognition software to respond to the idiosyncratic strum of a particular guitar. Where does this voice come from? In a way, it comes from God or Mother Nature or whatever name you choose to apply to those things we can’t quite fathom and can’t quite control.”

Part of what makes this book such a delight to read are the many characters that congregate in Hendersons guitar work shop. Allen St. John paints their portraits beautifully, and except for the lack of smells from working pieces of wood, I feel as if I am perched on a stool in that workshop, watching skilled hands do their thing, all the while the gentle banter flows back and forth, as jokes and stories are being told.

“‘Number 1 is the state of mind of the person building the guitar’.

I was stunned.

In a single sentence, he [T.J. Thompson] had articulated the hypothesis I had been gradually creeping toward. An instrument is the sum total of not only the builder’s experience, but his experiences. You need to be a good man to build a good guitar.

[…]

‘When people ask me how to build a better guitar, I always think and sometimes say, ‘Be a better person.’ You can’t keep your personality out of the work. It’s impossible.'”

Those paragraphs from pages 224 and 225 (of my hardcover edition from free press) are part of the insight that Jonathan Field riffed about, and when I read it, I remembered that I had actually blogged about this specific thing. Something with it resonated with me, and I think, perhaps, because I’d like for it to be universally true. I am not sure it is, but I would sure like for it to be!

The book I am blogging about is part of the book-reading challenge I’ve set for myself during 2019, to read and blog about 12 Swedish and 12 English books, one every other week, books that I already own.